Eye scans provide insight into kidney health

3D eye scans can reveal vital clues about kidney health that could help to track the progression of disease, research suggests.

The advance could revolutionise monitoring of kidney disease, which often progresses without symptoms in the early stages.

Experts say the technology has potential to support early diagnosis as current screening tests cannot detect the condition until half of the kidney function has been lost.

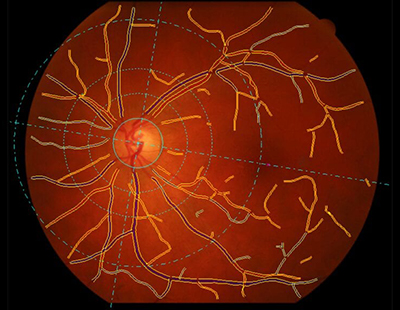

Researchers used highly-magnified images to detect changes to the retina – the layer of tissue at the back of the eye that senses light and sends signals to the brain. They found that the images offer a quick, non-invasive way to monitor kidney health.

The eye is the only part of the body where it is possible to view a key process called microvascular circulation – and this flow of blood through the body’s tiniest vessels is often affected in kidney disease.

Researchers at the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Cardiovascular Science investigated whether 3D images of the retina, taken using a technology called optical coherence tomography (OCT), could be used to identify and accurately predict the progression of kidney disease.

OCT scanners – used in most high street opticians – use light waves to create a cross-sectional picture of the retina, displaying each individual layer, within a few minutes.

The team looked at OCT images from 204 patients at different stages of kidney disease, including transplant patients, alongside 86 healthy volunteers.

They found that patients with chronic kidney disease had thinner retinas compared with healthy volunteers. The study also showed that thinning of the retina progressed as kidney function declined.

These changes were reversed when kidney function was restored following a successful transplant. Patients with the most severe form of the disease, who received a kidney transplant, experienced rapid thickening of their retinas after surgery.

More people than ever are at risk of kidney disease, which is often caused by other conditions that put a strain on the kidneys, including diabetes, high blood pressure and obesity.

With further research, regular eye checks could one day aid early detection and monitoring to prevent the disease from progressing. It could also allow patients to make lifestyle changes that reduce the risk of health complications, experts say.

Dr Neeraj Dhaun, Professor of Nephrology at the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Cardiovascular Science said: ” We hope that this research, which shows that the eye is a useful window into the kidney, will help identify more people with early kidney disease – providing an opportunity to start treatments before it progresses.

It also offers potential for new clinical trials and the development of drug treatments for a chronic disease that, so far, has proved extremely difficult to treat.”

The technology, supported by Heidelberg Engineering’s imaging platform, could also aid the development of new drugs, the research team says.

It could do so by measuring changes in the retina that indicate whether – and in what way – the kidney responds to potential new treatments.

The researchers say further studies – including longer-term clinical trials in larger groups of patients – are needed before the technology can be routinely used.

An estimated 7.2million people in the UK live with chronic kidney disease – more than 10% of the population. It costs the NHS around £7billion each year.

Dr Aisling McMahon, Executive Director of Research and Policy at Kidney Research UK added: ” Kidney patients often face invasive procedures to monitor their kidney health, often on top of receiving gruelling treatments like dialysis.

This fantastic research shows the potential for a far kinder way of monitoring kidney health. We are continuing to support the team as they investigate whether their approach could also be used to diagnose and intervene in kidney disease earlier.”

The study was funded by Kidney Research UK, and supported by Edinburgh Innovations, the University’s commercialisation service.

Read the paper published in Nature Communications.