Lasers offer hope to liver transplant process

Handheld laser devices that help surgeons quickly spot liver damage could transform transplant procedures, research suggests.

The non-invasive technique could provide medical staff with instant data on the health of donor livers and help them to identify which organs are suitable for transplant.

If widely adopted, the light-based tool could allow more livers to be transplanted safely and effectively experts say.

In the UK, liver disease is the third biggest cause of premature deaths. With demand for transplants growing and no matching increase in the donor pool, surgical teams must find efficient techniques to detect if organs are safe for transplant or not.

Currently, surgeons have no detailed or quantative way of assessing if a liver is healthy enough to transplant into a new person.

To assess if a donor’s liver is healthy and a good match for the recipient, the surgeon traditionally evaluates it using blood tests and inspects the organ by eye and feel. If the results are good, they transplant it – if not, it is discarded.

To improve the process, scientists and surgeons from the University of Edinburgh, the Edinburgh Transplant Centre and the University of Strathclyde used a new technique to detect damage in pigs’ livers – which are the closest anatomically to those of humans. Former Centre for Regenerative Medicine PhD student Dr Katie Ember first authored the paper.

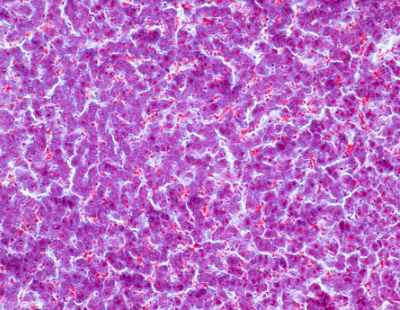

The team used a non-invasive laser light technique called Raman spectroscopy (RS) which examines tissue samples to help pinpoint the difference between healthy and damaged cells. In recent decades, RS has been used to detect breast, oesophageal and brain cancers.

By shining a laser onto tissue from pig liver biopsies and examining the light scattered back, the team was able to detect whether red blood cells had infiltrated the main body of the liver from its blood vessels – a form of damage known as congestion.

The quick results from the handheld RS spectrometer matched those from the more laborious ways of assessing a liver’s health, which involve blood biochemistry and gas analysis.

The tool was also used to shed light on the effectiveness of a new surgical technique called normothermic regional perfusion (NRP), which was pioneered by the surgical team in the Edinburgh Transplant Centre. The procedure uses a machine to re-establish blood circulation to donated organs after death.

Researchers used RS to confirm that NRP decreased congestion in the transplanted liver, giving them more detail in explaining the positive results seen in clinical use of NRP. The team is now working to translate these findings in a way that can aid clinical decision making in real time.

Dr Katherine Ember, Laboratory of Radiological Optics, Montreal, who carried out the analysis during her PhD at the Universities of Edinburgh and Strathclyde, said: ” We found that we could detect liver damage in a way that simply relies on shining a laser at liver tissue and collecting the light scattered back. We didn’t expect to find such a clear difference in Raman signal between damaged and undamaged liver tissue. It’s very exciting and will be fascinating to see whether this technology can be brought successfully into a clinical setting. This could enable liver damage to be detected early in the transplant procedure, allowing more livers to be transplanted safely and effectively.”

Professor Colin Campbell, School of Chemistry, University of Edinburgh added: ” This is a great opportunity for chemists to engage with medical colleagues in a way that is beneficial to the wider public.”

Professor Stuart Forbes, Centre for Regenerative Medicine, University of Edinburgh commented: ” This technology could allow surgeons to assess a donor liver’s function and spot potential problems in real time.”

Mr Gabriel Oniscu, Clinical Director of the Edinburgh Transplant Centre, who co-led the research project with Professor Campbell, said: ” Technologies, such as NRP, together with non-invasive real time assessment methods, are a real game changer that will allow surgeons to gain a better understanding of organ function prior to transplantation.”

The study is published in Hepatology and was funded via OPTIMA (EPSRC and MRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Optical Medical Imaging), an MRC Confidence in Concept Award and the Dutch Transplant Foundation.