Study published into MND drug riluzole

A team of researchers from the Anne Rowling Clinic and the Euan MacDonald Centre for motor neurone disease (MND) research, recently reviewed data around the prescription and use of riluzole for people with MND. Their findings encourage clinicians to offer riluzole to everyone newly diagnosed and provide information helpful to understand why people may stop taking the drug.

Riluzole is the only globally licensed drug treatment for the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) form of MND.

Trials and population studies have reported that the drug can extend life by 2–4 months and has very few side effects. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that clinicians offer riluzole to everyone diagnosed with ALS where it won’t interact badly with other medications or medical conditions.

For their research, the team, led by Dr Kiran Jayaprakash and Dr Stella Glasmacher, used data from the CARE-MND platform which holds the details of everyone diagnosed with MND in Scotland. CARE-MND is helping to improve clinical care across the country and enables healthcare professionals to audit the provision of MND care and treatment.

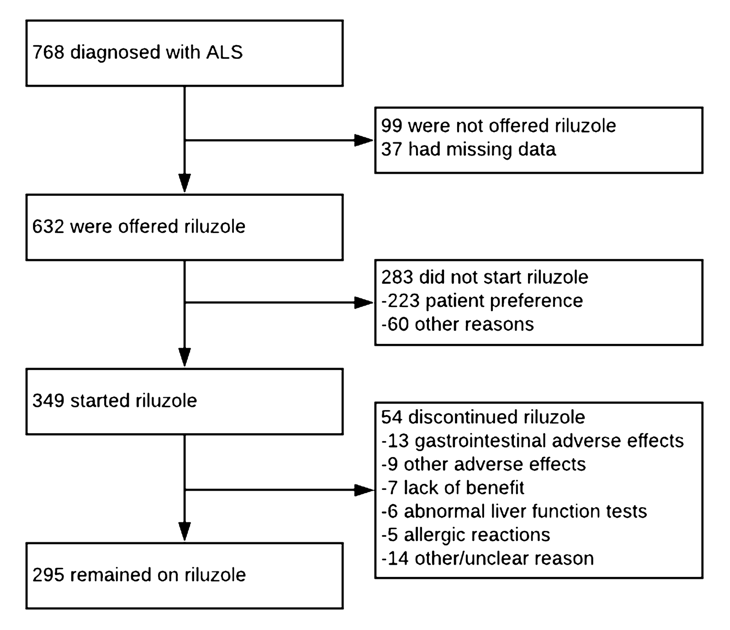

The data used for the study was from 768 people with ALS (diagnosed between January 2015 and April 2020).

87% of those diagnosed with ALS were offered riluzole and the majority of people started taking the drug but 39% chose not to. Older age was a significant factor in people not being offered riluzole and with not starting to take the drug

Of those who started riluzole, 15% (54) subsequently stopped taking the drug. The most common reasons for discontinuation were:

- 25% gastrointestinal adverse effects, including nausea, abdominal discomfort, constipation, and anorexia

- 13 % other adverse effects including fatigue/malaise

- 11% abnormal liver function

- 9% allergic reactions

- 13% of people stopped treatment due to their MND progressing and for the remainder of those who stopped, the reason was unclear

Conclusions

The proportion of people with ALS in Scotland offered riluzole being 87% is in keeping with previous estimates of 66–100% in the UK and 57–85% internationally.

Older people were less likely to take riluzole. This might be because of concerns around side effects or other medical conditions. It’s also possible that older people think that riluzole might do more harm than good when considering that it may only add a few months to their life expectancy.

However, recent research in Australia found that the survival benefit of riluzole is greater in older people with ALS. This Australian study, together with the findings from this research, emphasises the importance of offering riluzole to everyone diagnosed with ALS.

This Scottish study also offers an insight into the reasons people stop taking riluzole, which may inform the discussions clinicians have with people with ALS about taking the drug.

Flow-chart detailing the research findings